The application of radiocarbon dating to ground water analysis can offer a technique to predict the over-pumping of the aquifer before it becomes contaminated or overexploited, see sample study “Surface water contamination and remediation” (pdf).

Radiocarbon dating of groundwater is used in combination with the primary measurements of classical hydrological and chemical analyses. Radiocarbon dating will produce the best results when it involves multiple measurements or sequential sampling. The most useful data come from these comparisons and not from absolute ages.

In the case of multiple measurements, the apparent ages of the groundwater taken from pumps that are at varying distances from the aquifer outcrop could be a means of verifying flow rate and also indicate situations of over-pumping. In the case of sequential sampling of an individual well every six or twelve months, any changes in the apparent age of the water are plotted versus time. In particular, if the age of the water is getting younger with time, it would usually be due to a drawing-down of the more shallow water layers. Radiocarbon dating has the potential of giving advance notice of impending contamination by surface layer waters.

Radiocarbon dating of groundwater can give indications as to when the water was taken out of contact with the atmosphere, i.e. when it went underground. However, there are uncertainties present in calculating the percentage of carbonate species that originated from living plants in the aquifer outcrop and the atmosphere as opposed to that added by ancient carbonaceous deposits in the aquifer matrix. For this reason, radiocarbon dating of groundwater is most useful when repeated sampling occurs. In this case, obtaining absolute ages with their attendant uncertainties are not the primary numbers used in site interpretations. The uncorrected apparent ages are the primary numbers; they are used to compare with other apparent ages in the study. This will largely obviate the correction uncertainty. In all cases, the most useful data will come from these comparisons and not from absolute ages. Also, the uncorrected apparent ages can be interpreted as maximum ages, i.e. the real age of the groundwater is equal to or less than the apparent age.

By extracting the carbonates of the water for radiocarbon dating, the measurements can provide information on the recharge of underground deposits as well as flow directions and rates. This is valid for samples from 10 years old to 40,000 years old.

Surface water and rainfall infiltrating into the ground contain small amounts of carbon dioxide extracted from the air. Leaving the atmosphere, the water comes in contact with the soil air, where the partial pressure of vegetation (root-respiration) generated carbon dioxide is much higher. The radiocarbon content of these sources is the so-called “modern” level and is used for the reference in the age calculations. On average, from twenty to more than sixty wells are sampled in an aquifer. Less than ten wells is not a suitable study; in this case, interpretation of the ages will often be ambiguous.

In the case of aquifers containing fossil carbon, such as peat or brown coal, radiocarbon dating can give ambiguous results and these aquifers should not be studied with this dating technique. Water obtained from surface springs can provide useful apparent “ages”, but there is inevitably a problem with the carbon dilution correction because a large isotope effect can be generated when the carbon dioxide under pressure in the water readily bubbles out. In that case, a “best estimated age” cannot be calculated.

Disclaimer: This video is hosted in a third-party site and may contain advertising.

This video excerpt is part of Beta Analytic’s webinar – Isotopes 101: Dissolved Carbon.

As population density increases, demands on the aquifer will increase exponentially. Over-development can eventually lead to limited supply, with the greatest effects being to those districts farthest from the aquifers’ recharge zone.

Since under-utilized lands generally surround populated areas, housing and industrial development extends in directions reflecting the highest commercial yield. However, if the developing areas encroach onto the recharge zone, new wells drilled to satisfy the imminent demand could create shortages if pumping exceeds recharge.

By regularly monitoring the radiocarbon age of the water within a district’s well system, empirical evidence is available to realize overexploitation before it is out of control. Once residences or industries are established, it is very difficult to limit their water supply. Radiocarbon dating of the water provides a mechanism to monitor, understand, and control exploitation of the aquifer.

Figure 1 – Radiocarbon ages of groundwater as a function of distance from the aquifer’s outcrop. This illustrative case shows laminar groundwater flow curves with three pumping rates located at different distances from the outcrop limit. The last well is over-pumping and drawing water down from shallow levels.

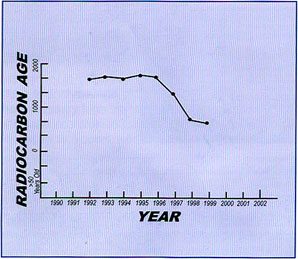

Time-based monitoring of the radiocarbon content of a well can reveal both the stability of, and the changes in, the source waters at the pump head. The younger radiocarbon ages of the water each year indicate younger waters are being drawn down from above. This could be caused, for example, by over-pumping of the well or by expanded well drillings in other areas. In either case, it indicates that eventually contaminated surface waters could enter the drinking supply.

Figure 2 – Radiocarbon ages of groundwater of an individual well sampled annually. In this illustrative case, a new pumping system was initiated at this well in 1995, substantially increasing the pumping rate in this area. Radiocarbon dating will have to be continued to see if there is an indication of increasing shallow water down-draft or if the curve flattens out before the surface water starts intruding.

The use of the radiocarbon dating method is best with annual or biannual sampling of individual wells. The values obtained would be compared to those of previous years. The most desirable situation is when the radiocarbon ages of sequentially sampled waters (every six or twelve months) from a particular well remain the same over the years.

Since radiocarbon occurs naturally in groundwater, this determination is made without any additions to the aquifer. Also, the determination is made before contamination enters the supply. This has strong economic and environmental implications for water resource management within and between districts.